Two Ex-Players Sue N.F.L. and Union Over Cuts in Disability Payments

Two former N.F.L. players have sued the league, the players’ union and the medical board those institutions jointly control for agreeing to reduce the disability payments they received for life by tens of thousands of dollars a year.

The complaint, filed in federal court in Washington, D.C., on Friday, stems from a provision in the 10-year collective bargaining agreement that the league and union ratified in March. In the deal, both sides agreed to cut disability payments to 400 or so former players whose doctors have determined they are unable to work.

The players now receive up to $138,000 a year. That amount will be reduced by the value of their Social Security disability benefits, which amounts to $2,000 or more per month, starting in January.

The decision to cut payments to some of the league’s most vulnerable former players has elicited outrage. Wives caring for former players on disability have criticized the N.F.L. on social media. Some members of the union’s executive committee said they did not fully recognize the implications of what they agreed to in the new labor deal. Active players have spoken up, too, most notably Eric Reid, a free-agent safety who said the union turned its back on the former players, a decision he called “disgraceful.”

In May, the N.F.L. Players Association said it planned to review the provisions in the new collective bargaining agreement that pertain to the reduction in benefits to permanently disabled former players.

Cleveland Browns center J.C. Tretter, the N.F.L.P.A. president, who was elected in March, said in his monthly newsletter that the union’s 11-member executive committee and leaders from among retired players would re-examine changes to the Total and Permanent Disability benefit “to fulfill our obligation to all of our members.” He also said the group had “a responsibility to review issues where we have fallen short.”

Two months later, the union has not announced any results from that review.

Tretter and other members of the executive committee will also reconsider a provision of the new labor agreement that allows only N.F.L. disability plan doctors to determine if a former player qualifies for benefits. For now, if a player is approved to receive Social Security disability benefits by an outside doctor, N.F.L. plan administrators will accept that diagnosis and release monthly benefits. This provision, which will be phased out under the agreement, could affect hundreds of additional players in the future.

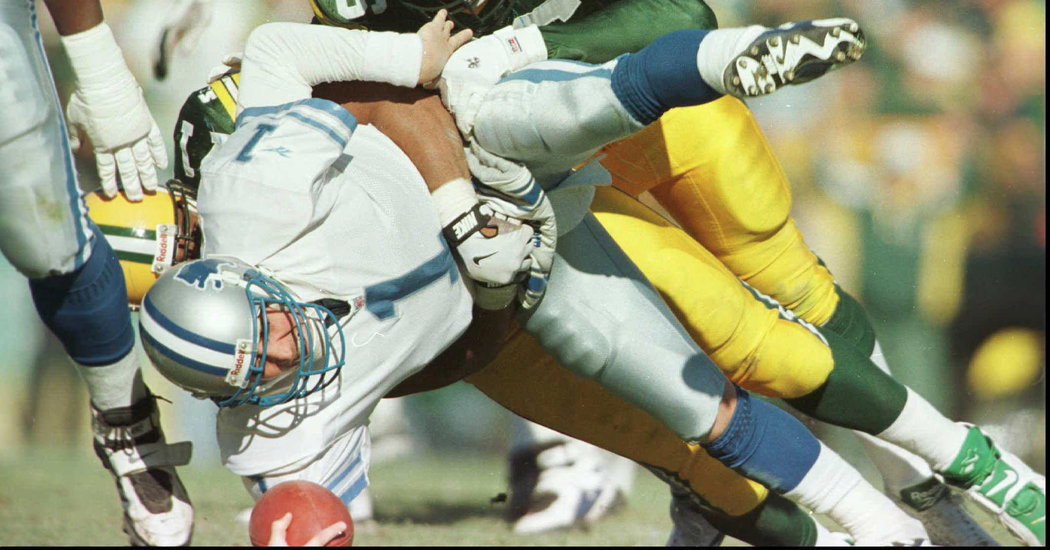

The union, the league and their disability review board will now have to consider the federal lawsuit brought by Aveion Cason, a running back who played for eight seasons, mostly in Detroit and St. Louis, and Donald Vincent Majkowski, a quarterback who spent 10 years with the Packers, Colts and Lions.

In their suit, they note that Commissioner Roger Goodell told Congress in 2007 that if a player was approved for Social Security disability payments, then the N.F.L. would honor that diagnosis. The new labor deal reverses that promise.

Cason and Majkowski also contend that language in the labor agreement was altered after it was signed, to the detriment of the former players who rely on disability payments. They say that the disability benefits that retired players receive were “for life.”

“It is elemental in sports that you do not change the rules of the game in the middle of the game,” Paul Secunda, a lawyer for the players, said in a statement. “Yet that is exactly what the N.F.L. and N.F.L.P.A. did to its most vulnerable members.”

The league did not respond to requests for comment, and the union said it would not comment at the moment.