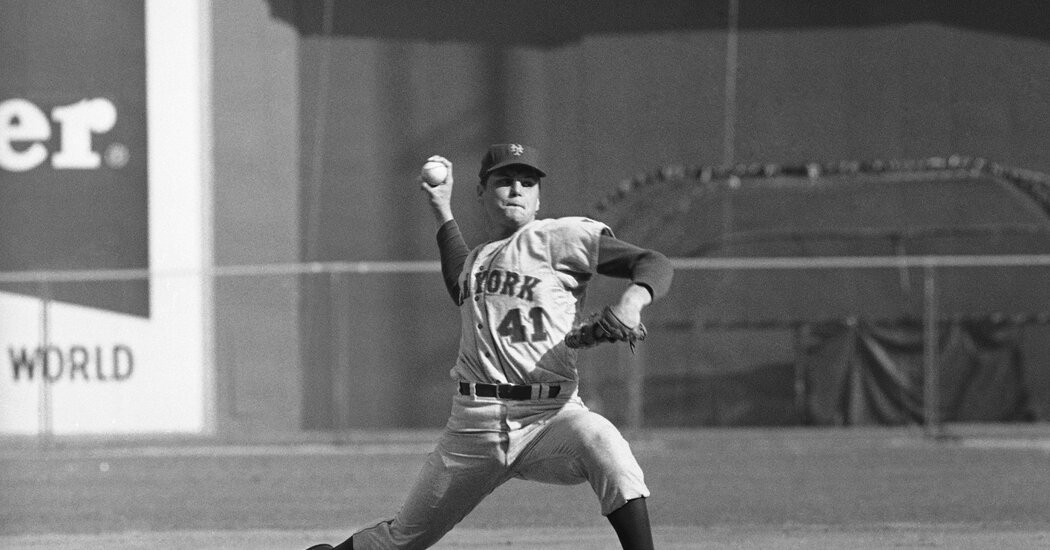

‘He Was the Perfect Pro’: Tom Seaver’s Senses Made Him a Baseball Great

The most fitting way to celebrate the life of Tom Seaver, the greatest Met of all, is with a wine glass in one hand and a baseball in the other. Seaver, who died on Monday at 75 years old from complications of Lewy body dementia and Covid-19, spent his retirement running a California vineyard. He was better known as a master pitching craftsman who felt the game in his bones.

“Somewhere on that ball there is a spot that feels as though it was born to be, the perfect place for your fingers,” Seaver wrote in his manual, “The Art of Pitching,” with Lee Lowenfish. “On those days when you are not pitching and are just watching your teammates play, hold a ball in your hand as you watch the game from the bench. Feel every aspect of the baseball.”

Try different seams and pressure points, Seaver instructed, don’t just imitate someone famous. Every hand is different, he said, but every pitcher must abide by two absolutes.

“Pitching is not a job for the physically timid or the mentally lazy,” he wrote — on the very first page. It is a mantra that might as well be inscribed on the Cy Young Award.

Seaver won three of those, in the Mets’ first World Series seasons — 1969 and 1973 — and again in 1975. After he was infamously traded to the Cincinnati Reds in 1977, he kept on rolling: a no-hitter in ’78, another taste of the playoffs in ’79, his 3,000th career strikeout in ’81. The Mets brought him back for 1983, but left him unprotected on their off-season roster.

The Chicago White Sox seized on the mistake, choosing Seaver as compensation for losing a free agent. It was a confusing and confounding way to lose the Franchise, as Seaver was known, but he found a way to make more magic in New York when he earned his 300th victory at Yankee Stadium in August 1985.

Tony La Russa, then the White Sox manager, had been ejected from that game and watched the late innings from a dugout tunnel, straining to see just a sliver of the field. With Dave Winfield coming up as the potential tying run in the eighth, La Russa’s trusted pitching coach, Dave Duncan, spoke at the mound with Seaver and catcher Carlton Fisk. Seaver looked tired, and he was.

“One thing about Tom — he would always tell you the truth,” La Russa said by phone Wednesday night. “So Dunc went out to talk to him and said, ‘Tom, I think you’ve had enough,’ and Tom said, ‘Yeah, I don’t think I have anything left.’

“But Fisk went up to him and said something like: ‘You’ve had enough? This is your ballgame! Nobody’s coming in from the bullpen to get Dave Winfield. This is you — you’re Tom Seaver!’”

This was one Hall of Famer challenging another Hall of Famer to pitch to a third Hall of Famer — and Seaver did not back down. He ran the count full to Winfield, then fanned him on a changeup and went on to complete the game.

“He was the most intelligent pitcher we’ve ever been around,” La Russa said. “He was a great competitor and had really good stuff, but as he got older, he was still great because he knew how to pitch. Like Greg Maddux, in a way — they would look at a hitter, know what the hitter was thinking and pitch away from it. He was the perfect pro.”

In those later years, especially, Seaver had an intuitive understanding of how to work around his limitations. Early in the 1985 season, after beating the Tigers in Detroit, Seaver noticed the home plate umpire, Jim Evans, at the hotel bar. He tapped Evans on the shoulder, thanked him for a job well done, but told him he had missed one pitch: a 1-1 fastball to Kirk Gibson in the middle innings. Evans was puzzled; he had called the pitch a strike.

“I don’t want you to call that pitch a strike,” Seaver said, as Evans recalled a few years ago. “That was a mistake. I got it up too high, like a ball or two above the waist, and I don’t want any batter to get used to swinging at that pitch. My fastball is still my best pitch, my bread-and-butter, but if I keep throwing that one up there, they’re going to kill me.”

Seaver would share such insights with teammates, with conditions. (“You had to earn his respect,” La Russa said. “He didn’t give it up carelessly.”) With the Reds, he saw something in Mario Soto, a young pitcher from the Dominican Republic who lacked polish but yearned to be great. Every morning at spring training, Soto would show up at 6 a.m., practicing his changeup alone against a concrete wall in the outfield.

“The only guy that discovered me and found out what I was doing was Tom Seaver,” Soto said a few years ago. “He was my teacher.”

Soto would sit beside Seaver during games, and at one point, Seaver asked him a question that seemed elementary: “Do you try to throw a strike with every pitch?”

Soto said he did; wasn’t that the whole point?

“No, no, no,” Seaver told him, and then Soto asked why. “‘Because you have pretty good control, and you want to take advantage of that,’” Soto recalled him saying. “From then on, I started doing that. From that day I knew I had good control, and then I started moving the ball in and out, up and down.”

In 1982 — his last year as Seaver’s teammate — Soto had the best strikeout-to-walk ratio in the majors.

Seaver finished his career with Boston in 1986, when a knee injury kept him off the World Series roster. But Seaver was there as the Red Sox fumbled away the title to the Mets, making him the only man to witness both of the Mets’ titles as a uniformed player at Shea Stadium.

The first championship had come in 1969, when Seaver’s 10-inning masterpiece in Game 4 helped the Mets to their famous miracle over the Baltimore Orioles. On Wednesday, when the world learned that Seaver had died, the Mets beat the Orioles again.

The stakes and the setting could hardly compare to the World Series. The game was played in Baltimore with empty stands, a grim reminder of the virus partly responsible for taking Seaver’s life.

But if it was a cosmic wink — the Mets and the Orioles, forever linked to vintage Seaver — why not go with it? Anything for a reason to think of the man at his best, to raise one last toast to Tom Terrific.